Extracting the most common words in Vietnamese

Table Of Contents

This post is the first in a series about tools for Vietnamese language learning tools. I will describe how we can extract the most common words for a number of large documents in the Vietnamese language. This list can then be used to create a vocabulary list for study.

For the whole project, see the dedicated project page.

Summary

In this post we will

- See where to download and how to process large documents in the Vietnamese language.

- Perform word segmentation to get the correct meanings of the words

- Count the words to get their frequencies to create a vocabulary list for language learning.

I published the code for this post on GitHub [1].

Goal

When learning a language, it is useful to know at least some words of the target language to understand it and be able to communicate with other people. But in which order should we learn these new words?

As a starting point, I assumed that learning the most frequent words would be pretty good. And indeed, I read some discussions [2], [3] where people have a similar approach to learning. In summary, learning the first 1000-2000 most common words lets you understand basic conversations, with more words allowing for more texts. Li [2] is painting a pretty bleak picture here, who estimates that you will need about 98% of the most common words, or 27,000 to become near-native!

I am aware that just learning the most common words will not suddenly help me become fluent (sadly). But it certainly would help me to read and immerse myself more without having to pick up the dictionary all the time.

So I downloaded the first Anki deck I found on the internet and started learning.

Problem

Pretty soon however, I found some problems with the Anki deck:

- There is no usage context on the cards, so it is pretty hard to remember them.

- The quality of translations is lacking for lots of cards.

- Using 5 minutes of research, I have no idea how these words were extracted in the first place. Seems to be quite random at times.

So I set out to improve my learning experience, and I wanted to create my own word frequency list for fun with the data I already had.

Note: While researching for this blog post, I realized that I really should have looked deeper into available resources. For example, I could’ve easily used this available word frequency list. Note sure what happened there and I missed it. Whoops 🤦! But at least I learned lots of things along the way.

Where to Find Which Words

So first, we will need to find some Vietnamese texts. I will describe which ones in the Corpora section. For people unfamiliar with this term: According to Wiktionary, a corpus in our context is “a collection of writings in the form of an electronic database used for linguistic analyses”.

Moreover, we can’t just use the raw words from the text. While the Vietnamese language does not have inflections like in English, we have to consider compound words, which Vietnamese utilizes heavily.

To illustrate this, let’s take the following example sentence:

Tôi sẽ thành công. (I will succeed.)

Here, we want to consider the words Tôi, sẽ and thành công as it means succeed, instead of its compounds. This task is called text or word segmentation and I will describe a way to do this quickly in the Word Segmentation section.

After this, we need to analyze the frequency of each segmented word and need to decide on a cut-off point. Although probably not really scientific, I chose the previously mentioned 98% mark for the rest of this post as a benchmark for the word extraction.

Solution

So to go ahead and extract these words we will need to:

- Select, download and preprocess the corpora.

- Apply word segmentation to all sentences to find the correct words.

- Count, merge and analyze the word frequencies for all documents.

1. Corpora

First, I want to mention that there is a great GitHub repository that summarizes various language processing resources for Vietnamese called “awesome Vietnamese NLP” [4] I wanted to include two types of corpus: First, texts that are more formal such as the news and Wikipedia, and second more casual conversations. For this I decided on the following corpora:

- Binhvq News Corpus [5], which includes news

- About 20 GB with about 3 billion words

- viwik18 [6], which is a dump of the Vietnamese Wikipedia from 2018

- About 98 MB with about 27 million words

- Facebook comment corpus, which was also included in the repo of the Binhvq News Corpus.

- About 444 MB with about 81 million words

- opensubtitles.org.Actually.Open.Edition [7] which is a (questionable?) dump of subtitle files from Open Subtitles

- About 379 MB with about 122 million words

We can just download the corpora and start working with them, as they already are in a readable format. Basically, they are just raw text, split across many small files. Except the subtitle files, which need some extra processing described in the next section.

I estimated the size with the du -sh command and used wc -w to count the number of words. So in total we have about 21 GB worth of data with more than 3 billion words.

Processing Open Subtitles Files

Processing the subtitle files involves a bit more work. I will only summarize the processing of this corpus, but I will probably write a whole blog post about it at some later point in time. To process this dataset, I applied the following steps:

- Extract all subtitles zips that have the Vietnamese language code (vi)

- Parse the SRT files and join them together to a single line. This is because a sentence might be distributed over multiple lines.

- Use a sentence segmentation model to extract the sentences and write them to a text file.

- A sentence segmentation model separates a single line of text into sentences.

With the text available, we proceed with the next step of processing: the word segmentation described earlier.

2. Word Segmentation

To perform the word segmentation, I chose to go for a non-deep learning approach, for which I have two reasons. First, I thought using a deep learning model would take forever to process everything. Second, after a quick search I found a paper [8] and its GitHub repo [9] written in Java that describes a “transformation rule-based learning model”. I’m not going to pretend to know what this exactly means, but “rule-based” sounds fast, and it’s supposed to be accurate enough.

I was not overly concerned with accuracy and hoped, due to the size of the texts, that it would average out. I was mostly concerned with getting it done, so I can actually stop procrastinating and start learning Vietnamese.

Let’s take a look at an example of what the results look like. If we have the following input (The police do not have time to continue verifying.)

Công an phường không có thời gian xác minh tiếp.

then the result will become

Công_an phường không có thời_gian xác_minh tiếp .

The compound words are combined with an underscore, which allows us to easily continue processing it.

Implementation Details

This section goes in a bit deeper on how I accomplished this. Feel free to skip it.

I haven’t worked with concurrent Java code before, and I feel a bit clunky with it. Once I started to use Scala for work, I could never look back. But I never really worked with concurrency in Scala before either at this point and was a bit intimidated by it.

It turns out, that it is actually quite simple in this case! All you have to do is use parallel collections. If we apply the algorithm in parallel to the files inside these collections, we can quite easily achieve some speedup (also known as an embarrassingly parallel problem). The resulting code is quite small, and I published it in the repo for this post.

Using this parallelized code, I was able to completely process all corpora quite quickly. I can’t be bothered to run it again, but it must have been less than 2 hours to process everything.

3. Analyzing Word Frequencies

So previously, we saw that Li [2] estimates we need 98% of the most common words to reach near near-native level, which I chose as a benchmark. Additionally, I want to group the words by the first, second, etc. thousand most common, so I can better track my progress.

To accomplish this, the rest of the processing is actually quite easy. What we need to do at this point is

- Count all segmented words from all documents.

- Merge them to a single file (and filter them by a list of valid words from a dictionary).

- Split this large file and group by the n-th thousand most common words.

If we just use the raw words, we will have some non-word characters and other nonsense in the list. To filter it, I used a word list constructed from the following dictionaries:

- Wiktextract [10] and its GitHub repo [11]

- This is a great project that parses Wiktionary XML dumps regularly and publishes them in a machine-readable JSONL format. It also includes entries for all languages. I will also use this for other parts of the project.

- The Free Vietnamese Dictionary Project [12]

- This seems to be a rather old project for a free Vietnamese dictionary from Uni Leipzig. The data is available for download, but it’s a bit of a hassle to use it directly. I wrote a parser for it to convert it to the same JSONL format as the Wiktextract project (missing reference).

All the steps above can be quite easily achieved by a couple of Python and Shell scripts that can be found in my repo [1].

After all of that, we will have a folder that contains the most frequent words, split conveniently into files of 1000 lines each. This folder will look like this:

$ ls

most_frequent_01.txt most_frequent_06.txt most_frequent_11.txt most_frequent_16.txt most_frequent_21.txt

most_frequent_02.txt most_frequent_07.txt most_frequent_12.txt most_frequent_17.txt most_frequent_22.txt

most_frequent_03.txt most_frequent_08.txt most_frequent_13.txt most_frequent_18.txt most_frequent_23.txt

most_frequent_04.txt most_frequent_09.txt most_frequent_14.txt most_frequent_19.txt most_frequent_24.txt

most_frequent_05.txt most_frequent_10.txt most_frequent_15.txt most_frequent_20.txt

And let’s see how the first 20 entries of the word frequencies look like :

và,41599096

của,41009489

các,29460924

là,29311617

có,27590205

trong,27345997

được,25208913

đã,24565107

cho,23718032

với,22242832

không,20117105

một,19513294

người,18231853

những,18118913

để,14998163

khi,14225072

này,14098654

ở,13816430

về,13204218

đến,13017067

Note: In most_frequent_01.txt the counts will be removed for a different feature. See Future Work.

That’s what we want. Neat! The frequency lists of each corpus, as well as the merged one, can be found in the releases of my GitHub repo [1].

Frequency Distribution

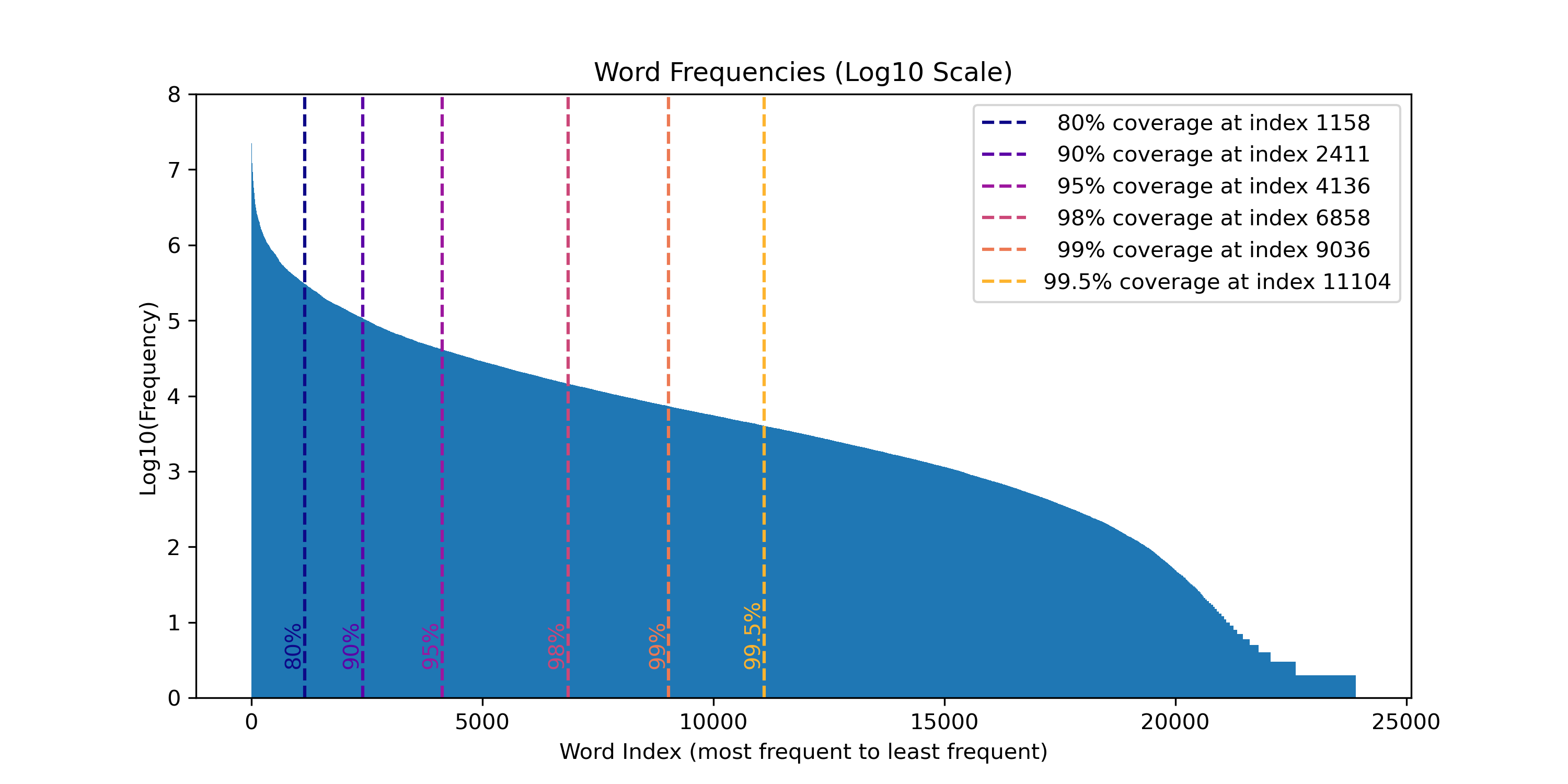

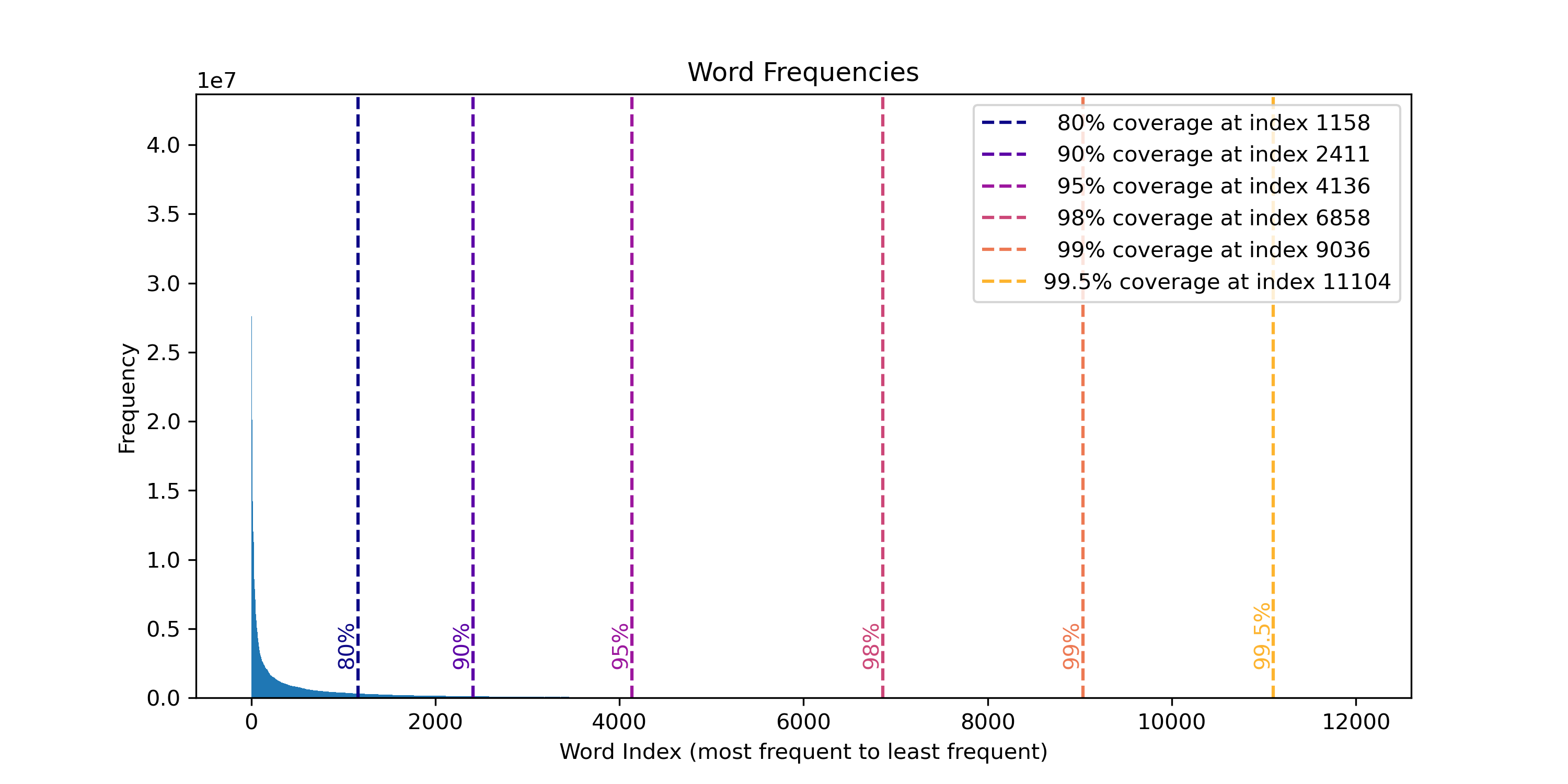

Having all extracted this data, I also wanted to see what the distribution of the words looked like. Additionally, I wanted to calculate the amount of words needed to hit the thresholds (80%, 90%, 95%, 98%, 99%, 99.5%) mentioned in the blog post by Li [2]. For this, I wrote a simple Python script which plots the rank of the word against its frequency and marks the thresholds. This is the result:

We see that we can’t see much because the distribution is very dense at the most common words. However, it seems like the vocabulary size for covering the threshold seems to be lower in Vietnamese. We previously said we need 27,000 to hit near-native level. If we assume the same threshold percentage in Vietnamese, then we would only need 7,000.

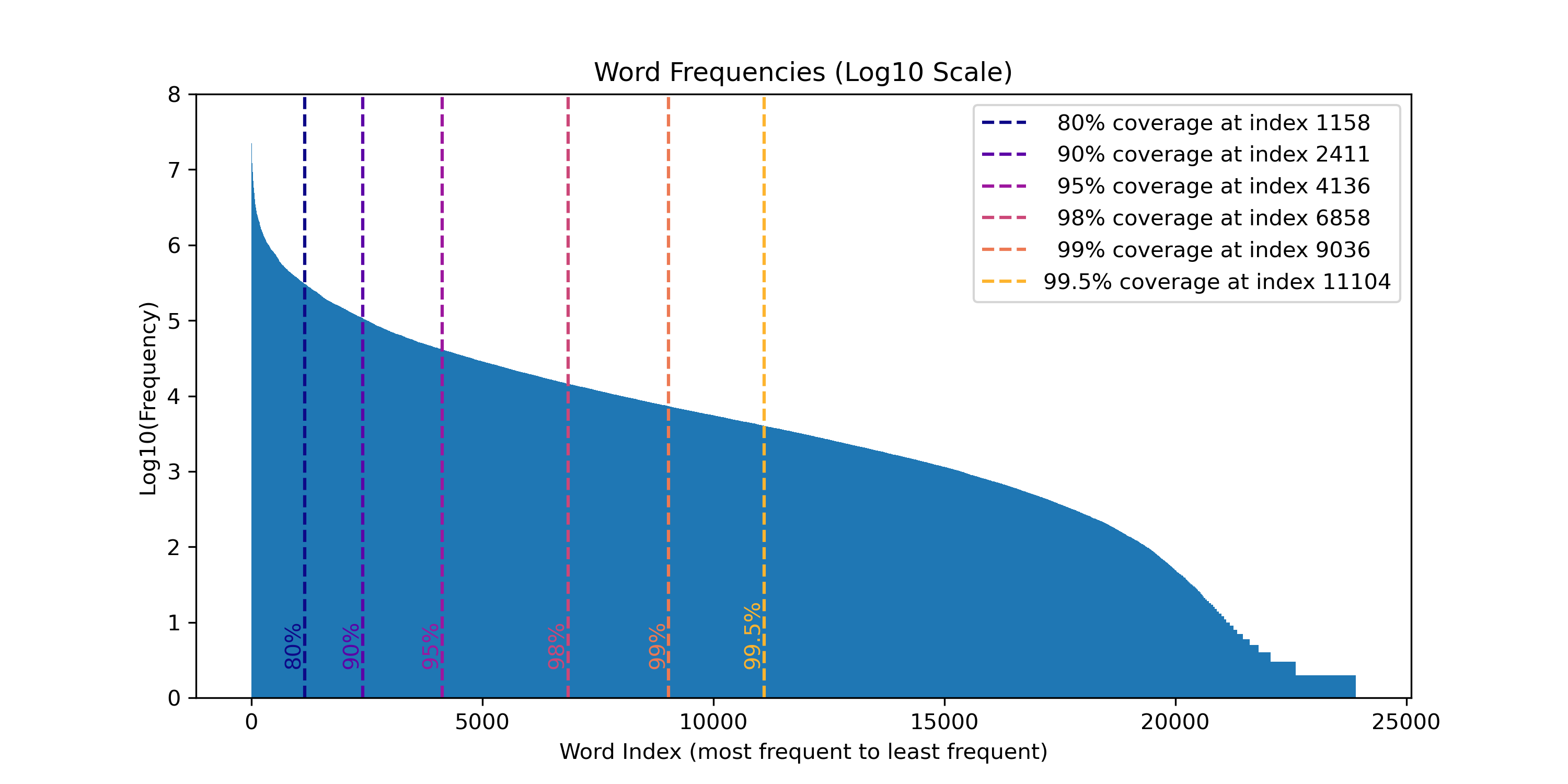

As a bonus, I plotted the whole thing again on a Log10 scale to get a prettier plot:

How we can read this is we look at the tenth power at the index to get a feel for the magnitude. For example, at index 0, we have more than \(10^7\), so tens of millions of occurences, while at the 98% mark we are at about \(10^4\) meaning tens of thousands.

Conclusion and Future Work

To conclude this post, we have taken a look at how to process corpora in the Vietnamese language and extract its word frequencies using tools found on GitHub, as well as some scripts that I wrote and published on GitHub [1]. After that, we found out how many of the most frequent words we need to reach a certain level of proficiency, which are about 7,000.

In the next post, we will tackle the next problem. Now that we have all the words, it would be a real pain to manually add them to Anki. So what can we do? Of course, spend a significant amount of time automating it. It’s actually pretty worth it though, I swear!

References

-

[1]“DevinTDHa/vn-Nlp-Exp: NLP Experiments for the Vietnamese Language.” Accessed: Oct. 30, 2024. [Online]. Available at: https://github.com/DevinTDHa/vn-nlp-exp/tree/main.

-

[2]B. Li, “The Power Law Distribution and the Harsh Reality of Language Learning.” Lucky’s Notes, Jul. 12, 2017, Accessed: Oct. 27, 2024. [Online]. Available at: https://luckytoilet.wordpress.com/2017/07/12/the-power-law-distribution-and-the-harsh-reality-of-language-learning/.

-

[3]“The Size of Vocabulary to Set as a Goal. - A Language Learners’ Forum.” 2021, Accessed: Oct. 28, 2024. [Online]. Available at: https://forum.language-learners.org/viewtopic.php?t=16463.

-

[4]D. Huynh, “Vndee/Awsome-Vietnamese-Nlp.” Oct. 21, 2024, Accessed: Oct. 27, 2024. [Online]. Available at: https://github.com/vndee/awsome-vietnamese-nlp.

-

[5]B. Vương Quốc, “Binhvq/News-Corpus: Corpus Tiếng Việt.” 2024, Accessed: Oct. 27, 2024. [Online]. Available at: https://github.com/binhvq/news-corpus.

-

[6]“NTT123/Viwik18: Vietnamese Text Dataset - Wikipedia vi 2018.” 2018, Accessed: Oct. 27, 2024. [Online]. Available at: https://github.com/NTT123/viwik18.

-

[7]“‘5,719,123 Subtitles from Opensubtitles.Org’ or ‘Opensubtitles.Org.Actually.Open.Edition.2022.07.25.’” Accessed: Oct. 29, 2024. [Online]. Available at: http://archive.org/details/opensubtitles.org.Actually.Open.Edition.2022.07.25.

-

[8]T. Vu, D. Q. Nguyen, M. Dras, and M. Johnson, “VnCoreNLP: A Vietnamese Natural Language Processing Toolkit,” in Proceedings of the 2018 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Demonstrations, Jun. 2018, pp. 56–60, doi: 10.18653/v1/N18-5012.

-

[9]V. CoreNLP, “Vncorenlp/VnCoreNLP.” Oct. 24, 2024, Accessed: Oct. 29, 2024. [Online]. Available at: https://github.com/vncorenlp/VnCoreNLP.

-

[10]T. Ylonen, “Wiktextract: Wiktionary as Machine-Readable Structured Data,” in Proceedings of the Thirteenth Language Resources and Evaluation Conference, Jun. 2022, pp. 1317–1325, Accessed: Oct. 30, 2024. [Online]. Available at: https://aclanthology.org/2022.lrec-1.140.

-

[11]T. Ylonen, “Tatuylonen/Wiktextract.” Oct. 30, 2024, Accessed: Oct. 30, 2024. [Online]. Available at: https://github.com/tatuylonen/wiktextract.

-

[12]D. Ho Ngoc, “Free Vietnamese Dictionary Project.” 2004, Accessed: Oct. 30, 2024. [Online]. Available at: https://www.informatik.uni-leipzig.de/ duc/Dict/install.html.